DROPS Representation¶

Beyond Vectors: The DROPS Representation of Operators¶

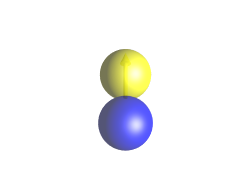

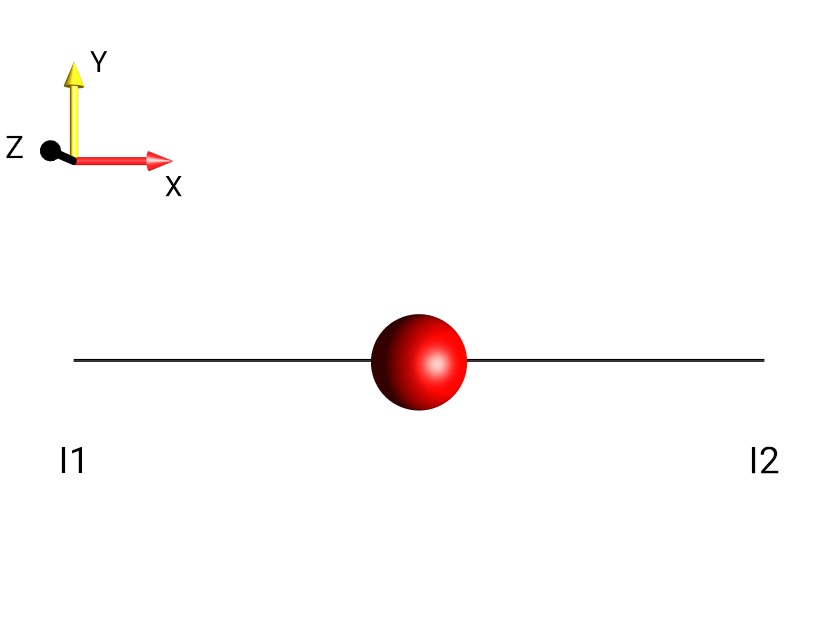

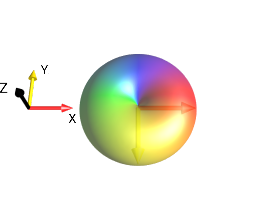

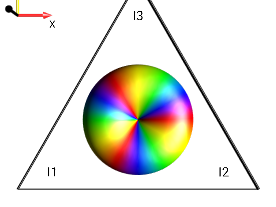

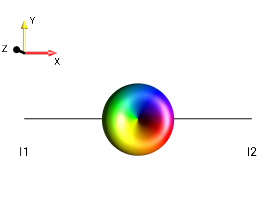

The states of uncoupled spins ½ can be completely described using three-dimensional Bloch vectors (commonly called “magnetization vectors” in NMR). However, to describe the general and more interesting case of coupled spins, the Bloch vector picture is insufficient and more advanced concepts based on operators (such as product operators, density operators, Hamiltonian operators etc…) are used. While these operators and their time evolution can easily be calculated and manipulated by computers, they are difficult to visualize. In the DROPS representation [GARON2015], operators are displayed as a set of droplets, where each droplet corresponds to some operators involving a defined set of spins (individual spins, pairs of spins, etc…)

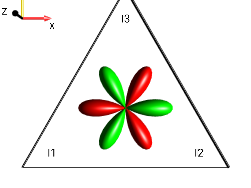

Fig. 54 \(I_{1x}+I_{1x}I_{2y}+I_{2x}\)¶

This chapter presents the general properties of the DROPS representation. Familiarity with the shapes of certain characteristic droplets requires a little practice, but it can be fun and highly rewarding. DROPS provides a very intuitive visualization of spin dynamics which is helpful in understanding the concepts of magnetic resonance spectroscopy that form the basis of modern pulse sequences design, such as coherence order, phase cycles, polarization transfer etc… In the following, we summarize and illustrate the most important properties of the DROPS display. For the mathematical background of the DROPS representation, see Mathematical Background of the DROPS Visualization.

Droplets representing Linear Operators¶

The droplets in Table 2 are closely related to the Bloch vector picture.

|

|

|

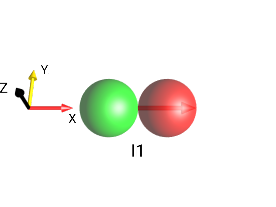

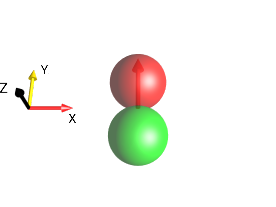

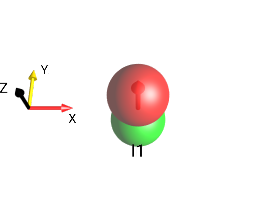

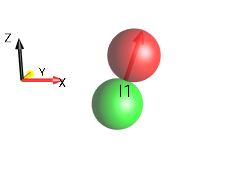

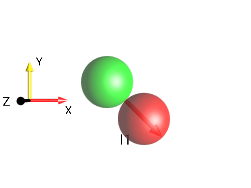

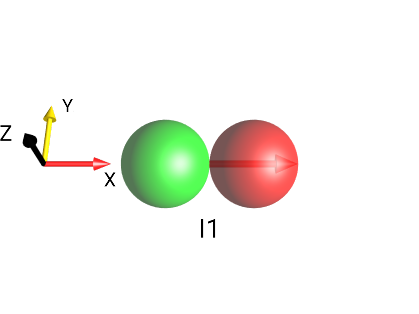

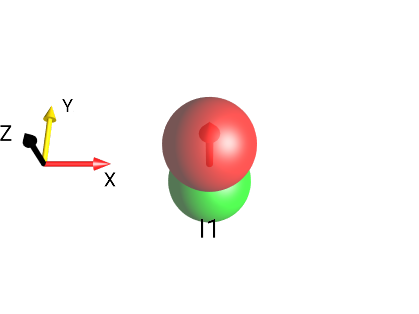

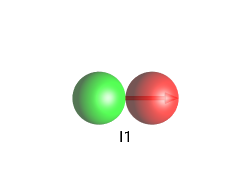

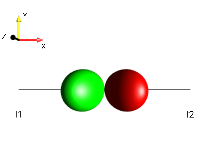

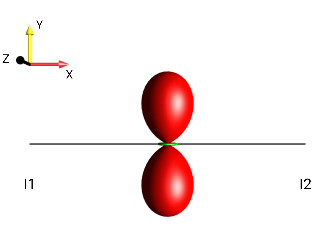

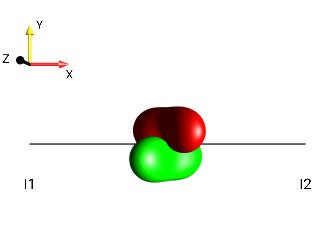

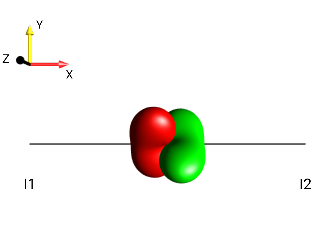

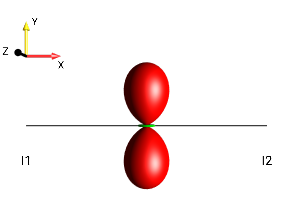

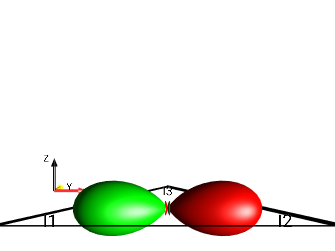

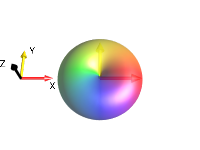

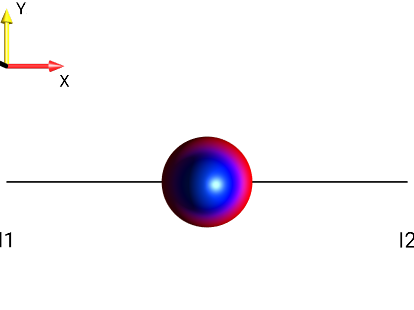

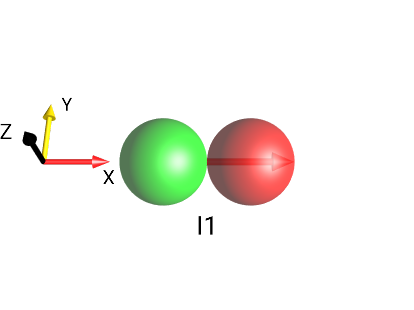

For a linear Cartesian operator (i.e. operators such as \(I_{1x}\) or \(I_{1z}\) which involve only a single spin) the corresponding droplet consists of two spheres: a positive sphere (red) and a negative sphere (green). As illustrated below, the same is true for sums (Fig. 55) and differences (Fig. 56) of such operators having real prefactors (associated with the same spin, e.g. \(I_1\)).

Such combinations of linear operators can also be represented as a single vector (the Bloch vector or magnetization vector in the case of the density operator).

Fig. 55 \(0.3 \cdot I_{1x}+0.9 \cdot I_{1z}\)¶ |

Fig. 56 \(0.717 \cdot I_{1x}-0.717 \cdot I_{1y}\)¶ |

An important property of the DROPS representation is that the Bloch vector is inscribed in the red sphere and the base of the vector touches the green sphere. Hence, the orientation of the droplet (defined as the direction of the vector connecting the centers of the green and red spheres) is always identical to the orientation of the corresponding Bloch vector.

For a single spin, the DROPS Representation is closely related to the well-known vector picture. Therefore, a droplet representing the linear operators associated with a given spin is shown in transparent mode and the corresponding vector is shown simultaneously, inside the droplet.

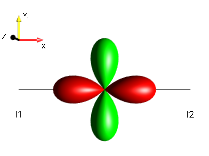

Droplets of Cartesian Product Operators Are Real-Valued¶

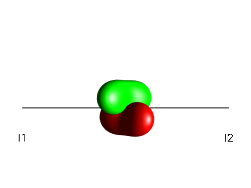

Droplets representing standard Cartesian product operators are real and thus can have only the colors red (for positive values) and/or green (for negative values). The color coding of the droplets is explained in Color Code for Droplets.

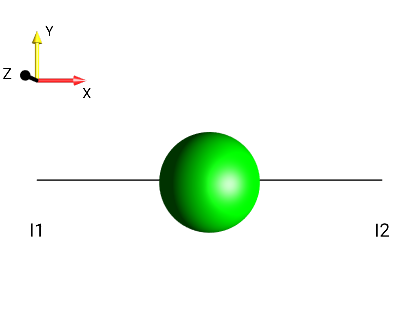

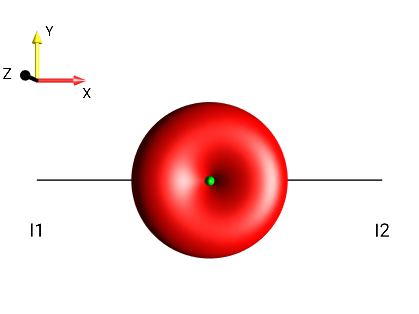

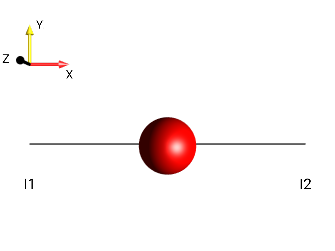

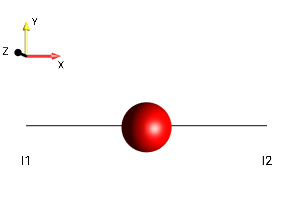

Table 3 shows some individual Cartesian product operators, involving 0 spins (term proportional to the identity operator E, Fig. 57), a single spin (linear operators Fig. 59, Fig. 61) and two spins (bilinear operators Fig. 58, Fig. 60, Fig. 62).

Fig. 57 \(Id\)¶ |

Fig. 58 \(2I_{1x}I_{2x}\)¶ |

Fig. 59 \(I_{1x}\)¶ |

Fig. 60 \(2I_{1x}I_{2y}\)¶ |

Fig. 61 \(I_{1z}\)¶ |

Fig. 62 \(2I_{1x}I_{2z}\)¶ |

Droplets of Hermitian Operators Are Red/Green¶

Droplets representing Hermitian operators (corresponding to real combinations of Cartesian product operators) can be recognized easily because they only have the colors red and green. Examples of some droplets representing Hermitian operators are shown in Table 4.

Fig. 63 \(2I_{1y}I_{2x}-2I_{1x}I_{2y}\)¶ |

Fig. 64 \(2I_{1x}I_{2x}+2I_{1y}I_{2y}\)¶ |

Fig. 65 \(2I_{1x}I_{2x}-2I_{1y}I_{2y}\)¶ |

Fig. 66 \(2I_{1x}I_{2y}+2I_{1y}I_{2x}\)¶ |

Fig. 67 \(2I_{1x}I_{2x}+2I_{1y}I_{2y}+2I_{1z}I_{2z}\)¶ |

Fig. 68 \(I_{1x}I_{2x}+I_{1y}I_{2y}-2I_{1z}I_{2z}\)¶ |

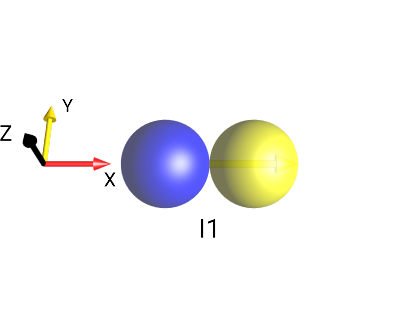

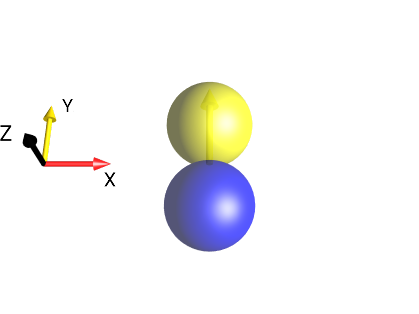

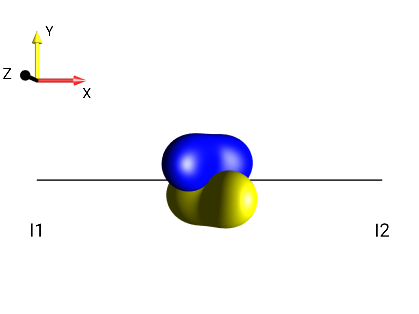

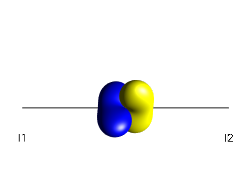

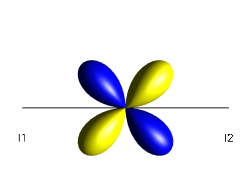

Droplets of Skew-Hermitian Operators Are Yellow/Blue¶

Multiplying Hermitian operator by the imaginary unit \(i\) results in so-called skew-Hermitian operators. The corresponding droplet functions are purely imaginary. Their droplets can only have the colors yellow (if the imaginary part of the droplet function is positive) or blue (if the imaginary part of the droplet function is negative). Examples of some droplets representing skew-Hermitian operators are shown in Table 5.

Fig. 69 \(i \cdot I_{1x}\)¶ |

Fig. 70 \(i \cdot I_{1y}\)¶ |

Fig. 71 \(i \cdot 2I_{1x}I_{2z}\)¶ |

Fig. 72 \(i \cdot 2I_{1y}I_{2z}\)¶ |

Droplets of Operators Consisting of Hermitian and Skew-Hermitian Components¶

Table 6 presents important examples of operators which are neither purely Hermitian nor purely skew-Hermitian, i.e. they can be decomposed into Hermitian and skew-Hermitian parts.

Fig. 73 \(I_{1}^{+}\)¶ |

\(=\) |

Fig. 74 \(I_{1x}\)¶ |

\(+\) |

Fig. 75 \(i \cdot I_{1y}\)¶ |

Fig. 76 \(2I_{1}^{+}I_{2z}\)¶ |

\(=\) |

Fig. 77 \(2I_{1x}I_{2z}\)¶ |

\(+\) |

Fig. 78 \(i \cdot 2I_{1y}I_{2z}\)¶ |

Fig. 79 \(2I_{1}^{+}I_{2}^{+}\)¶ |

\(=\) |

Fig. 80 \(2I_{1x}I_{2x}-2I_{1y}I_{2y}\)¶ |

\(+\) |

Fig. 81 \(i \cdot (2I_{1x}I_{2y}+2I_{1y}I_{2x})\)¶ |

Non-Selective Rotations of Operators Simply Rotate the Droplets¶

Rotating an operator by a given angle about a given axis also rotates the corresponding droplets by the same angle about the same axis. This is one of the most important features of the DROPS Representation. For example, rotating the operator \(2I_{1x}I_{2x} - 2I_{1y}I_{2y}\) by 45° about the z axis results in \(2I_{1y}I_{2x} + 2I_{1x}I_{2y}\) and an additional rotation by 90° about the x axis results in \(2I_{1z}I_{2x} + 2I_{1x}I_{2z}\).

Note

it is far more intuitive to recognize rotations based on the initial and final DROPS representations rather than based on the initial and final product operators.

Fig. 82 \(2I_{1x}I_{2x}-2I_{1y}I_{2y}\)¶ |

\(\Longrightarrow\) (45°z) |

Fig. 83 \(2I_{1y}I_{2x}+2I_{1x}I_{2y}\)¶ |

\(\Longrightarrow\) (90°x) |

Fig. 84 \(2I_{1z}I_{2x}+2I_{1x}I_{2z}\)¶ |

Characteristic Droplets of Cartesian Product Operators Involving Two Spins¶

Table 8 shows all of the droplets corresponding to two-spin operators.

Fig. 85 \(2I_{1x}I_{2x}\)¶ |

Fig. 86 \(2I_{1x}I_{2y}\)¶ |

Fig. 87 \(2I_{1x}I_{2z}\)¶ |

Fig. 88 \(2I_{1y}I_{2x}\)¶ |

Fig. 89 \(2I_{1y}I_{2y}\)¶ |

Fig. 90 \(2I_{1y}I_{2z}\)¶ |

Fig. 91 \(2I_{1z}I_{2x}\)¶ |

Fig. 92 \(2I_{1z}I_{2y}\)¶ |

Fig. 93 \(2I_{1z}I_{2z}\)¶ |

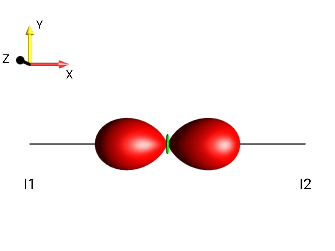

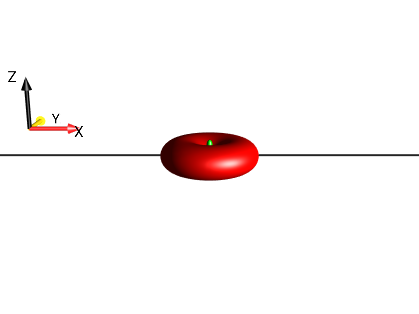

Droplets of Cartesian Product Operators of the Form \(2I_{1a}I_{2a}\)¶

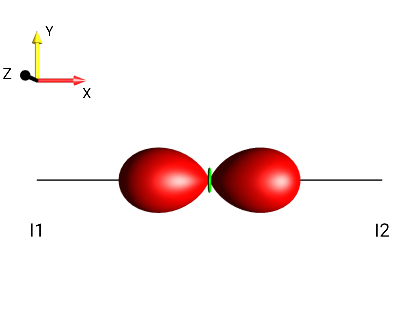

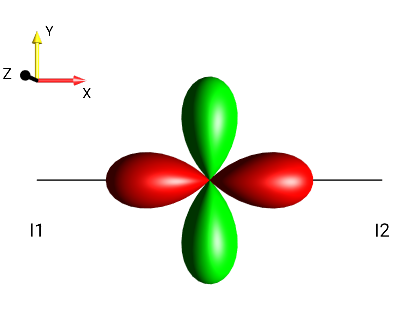

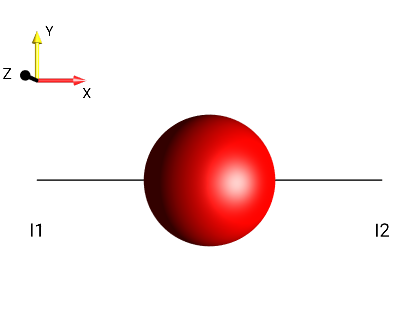

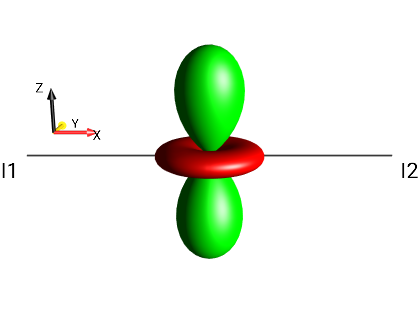

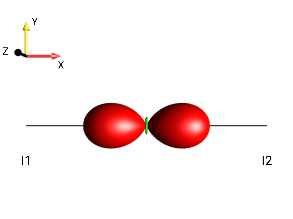

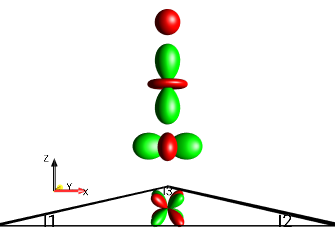

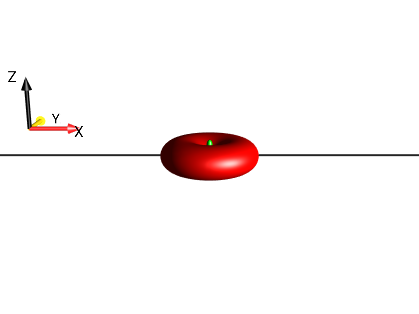

As shown along the diagonal in Table 8, the bilinear product operators \(2I_{1x}I_{2x}\), \(2I_{1y}I_{2y}\), and \(2I_{1z}I_{2z}\), of the general form \(2I_{1a}I_{2a}\) with \(a ∈ {x, y, z}\), easily be recognized by their elongated shapes along the \(a\) axis . They consist of two red (positive) lobes (oriented in the direction of \(a\) and \(-a\), respectively), and a small green (negative) toroidal shape encircling the \(a\) axis.

Fig. 94 \(2I_{1x}I_{2x}\)¶ |

Fig. 95 \(2I_{1y}I_{2y}\)¶ |

Fig. 96 \(2I_{1z}I_{2z}\)¶ |

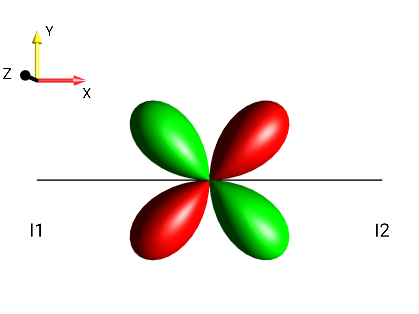

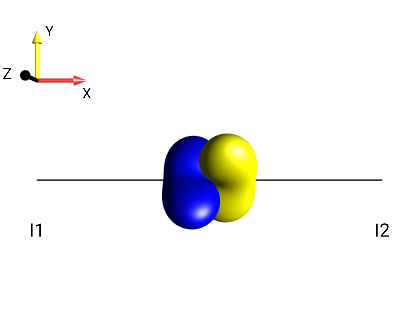

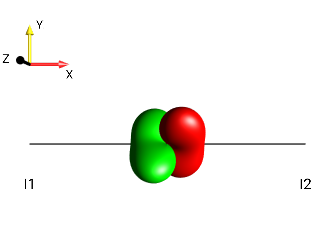

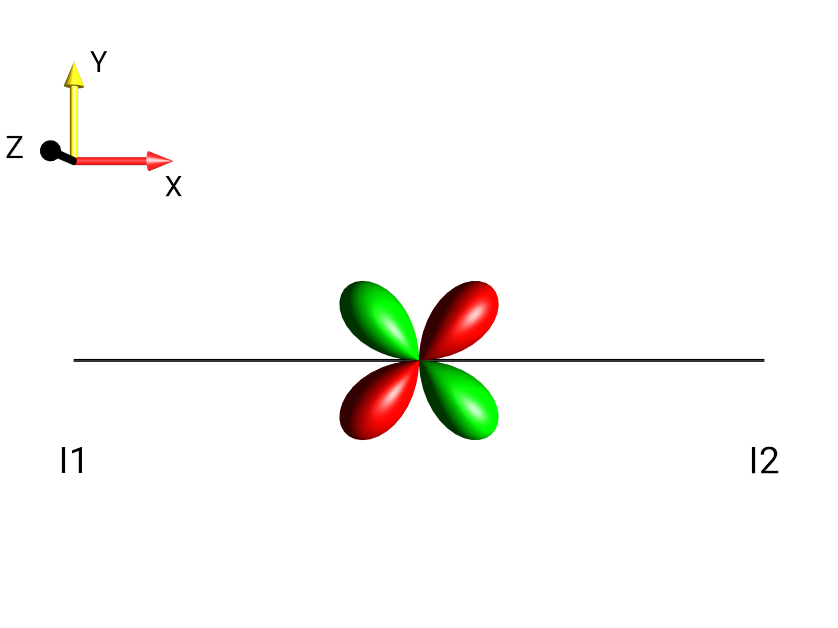

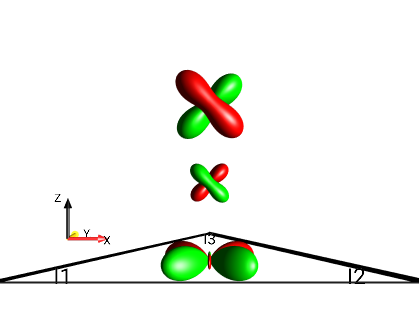

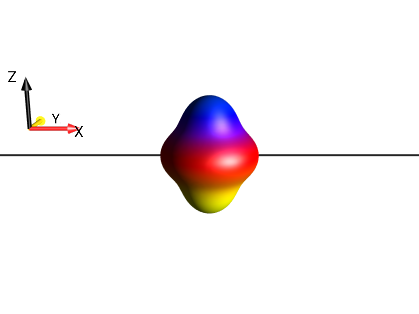

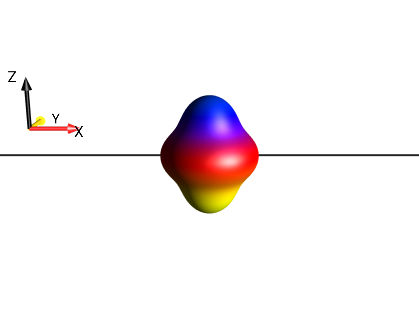

Droplets of Cartesian Product Operators of the Form \(2I_{1a}I_{2b}\)¶

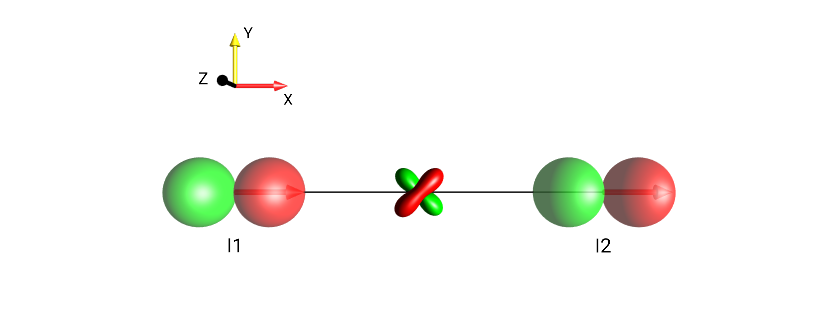

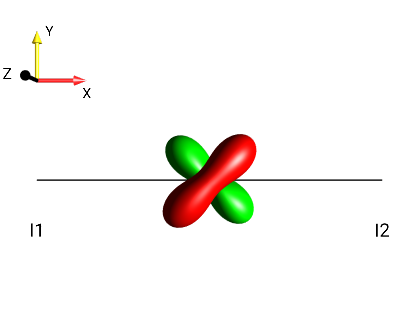

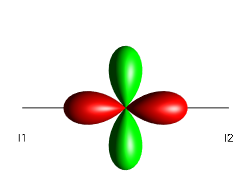

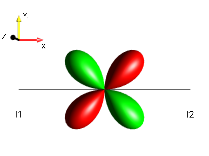

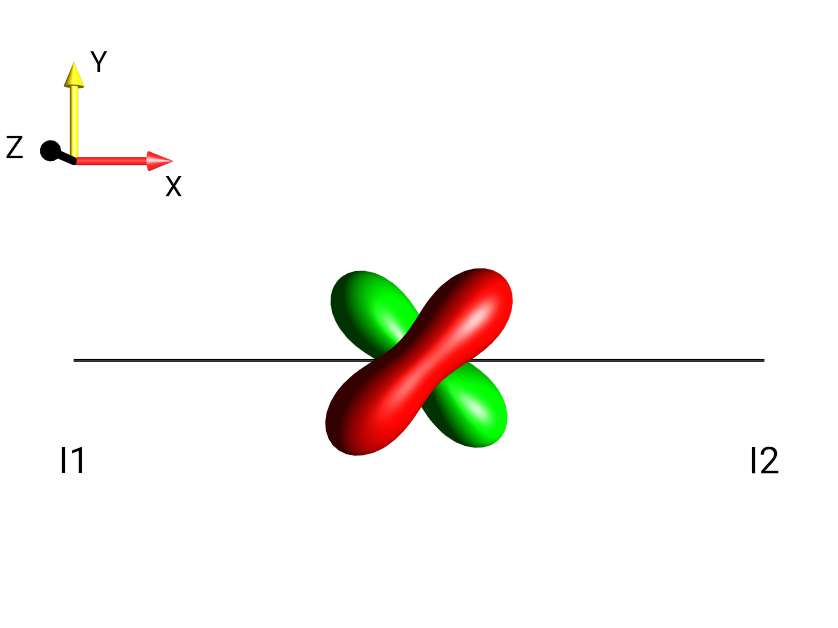

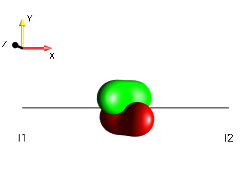

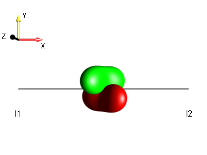

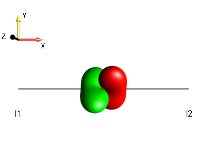

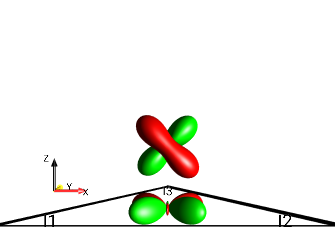

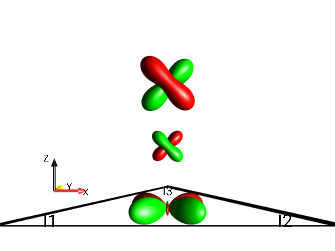

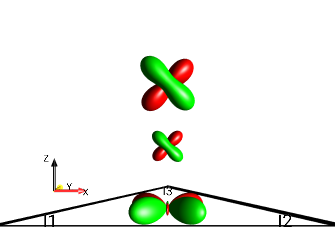

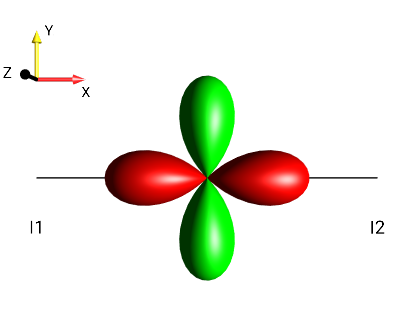

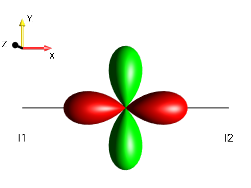

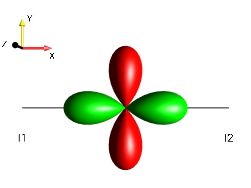

The operators \(2I_{1a}I_{2b}\) with \(a≠b\) and \(a, b ∈ {x, y, z}\) are represented by a droplet with two bean-shaped lobes of opposite signs. There is a red (positive) lobe and a green (negative) lobe. As all operators of this form (\(2I_{1a}I_{2b}\)) can be obtained by non-selective 90° rotations of e.g. \(2I_{1x}I_{2y}\) (see Challenge 8).

Composition¶

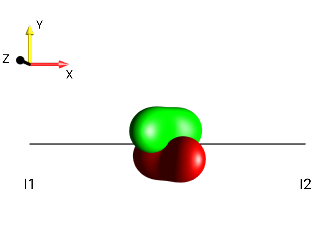

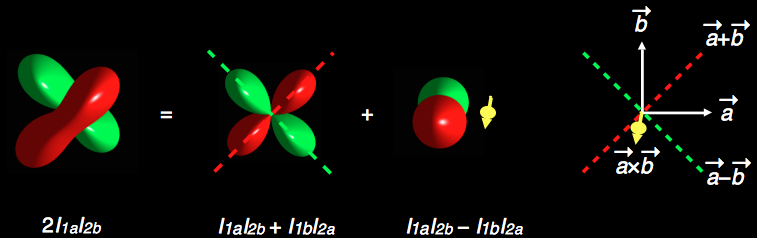

Here we focus on the operator \(2I_{1x}I_{2y}\) to understand the origin of the characteristic shape of these droplets. \(2I_{1x}I_{2y}\) can be expressed as a linear combination of the double-quantum operator \(DQy = I_{1x}I_{2y}+I_{1y}I_{2x}\) (symmetric with respect to an exchange of the two spins) and the zero-quantum operator \(ZQy = -I_{1x}I_{2y}+I_{1y}I_{2x}\) (anti-symmetric with respect to an exchange of the two spins):

\(2I_{1x}I_{2y} = DQy - ZQy = DQy + (-ZQy) = (I_{1x}I_{2y} + I_{1y}I_{2x}) + (I_{1x}I_{2y}-I_{1y}I_{2x})\)

Visually:

Fig. 97 \(2I_{1x}I_{2y}\)¶ |

\(=\) |

\(DQy\)

Fig. 98 \(I_{1x}I_{2y}+I_{1y}I_{2x}\)¶ |

\(+\) |

\(-ZQy\)

Fig. 99 \(I_{1x}I_{2y}-I_{1y}I_{2x}\)¶ |

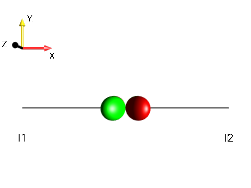

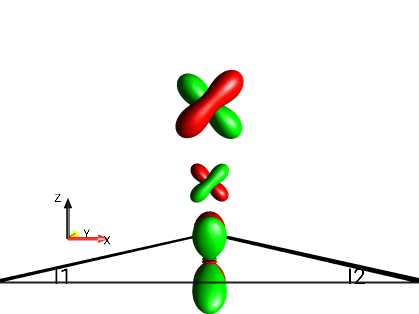

Anti-Phase Cartesian Product Operators¶

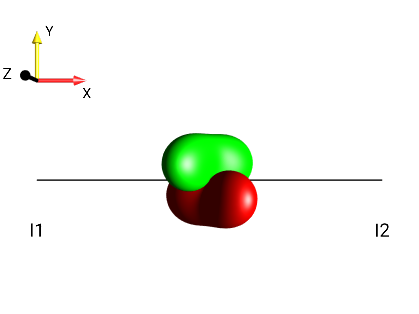

Similar to \(2I_{1x}I_{2y}\), the antiphase operator \(2I_{1x}I_{2z}\) can be expressed as a sum of a symmetric and an anti-symmetric term:

Fig. 100 \(2I_{1x}I_{2z}\)¶ |

\(=\) |

Fig. 101 \(I_{1x}I_{2z}+I_{1z}I_{2x}\)¶ |

\(+\) |

Fig. 102 \(I_{1x}I_{2z}-I_{1z}I_{2x}\)¶ |

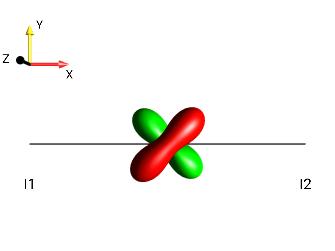

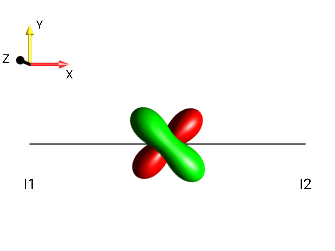

Identifying Kissing Bean Droplets¶

As illustrated in Fig. 103, an operator of the form \(2I_{1a}I_{2b}\), where \(a≠b\) and \(a, b ∈ {x, y, z}\), can always be written as a sum of the form \(2I_{1a}I_{2b} = (I_{1a}I_{2b} + I_{1b}I_{2a}) + (I_{1a}I_{2b} - I_{1b}I_{2a})\). The droplet corresponding to the symmetric term in the first bracket is “X-shaped” and consists of two red (positive) lobes oriented along the axis of the vector sum a+b (dashed red line) and two green (negative) lobes oriented along the axis of the vector difference \(a-b\) (dashed green line). The droplet corresponding to the anti-symmetric term in the second bracket consists of a red (positive) and a green (negative) sphere, where the red sphere is displaced relative to the green sphere in the direction given by the cross product a×b (yellow arrow). In the DROPS representation of \(2I_{1a}I_{2b}\), the red (and green) lobes of (\(I_{1a}I_{2b} + I_{1b}I_{2a}\)) and (\(I_{1a}I_{2b} - I_{1b}I_{2a}\)) merge, forming the characteristic droplet consisting of a red and green bean-shaped lobe.

Fig. 103 Identifying kissing-bean droplets.¶

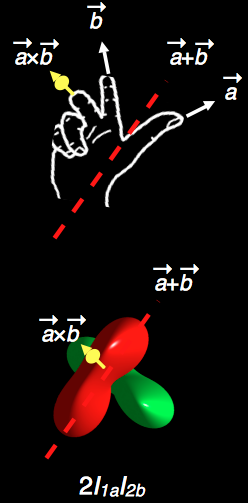

Right-hand Rule¶

The shape and color of the droplet representing a Cartesian product operators of the form \(2I_{1a}I_{2b}\), where \(a≠b\) and \(a, b ∈ {x, y, z}\), can be constructed and analyzed using the following right-hand rule:

Point the thumb of your right hand in the direction of the unit vector \(a\) and the index finger in the direction of \(b\).

The bisector of the angle formed by the thumb and index finger defines the axis of the vector sum \(a+b\) (dashed red line). This defines the long axis of the bean-shaped red lobe of the droplet. (Orthogonal to the red axis, the long axis of the green bean-shaped lobe is oriented along the axis defined by \(a-b\).)

Relative to the center of the droplet, the red lobe is displaced in the direction given by the cross product \(a×b\) (yellow arrow), which is given by the orientation of the middle finger of your right hand. (The green lobe is displaced in the opposite direction.)

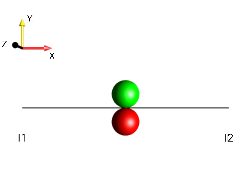

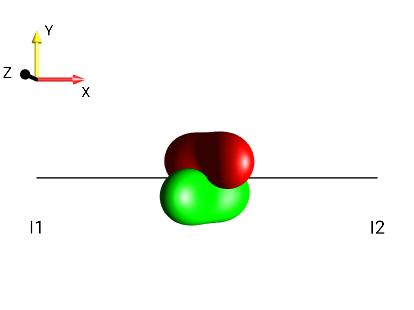

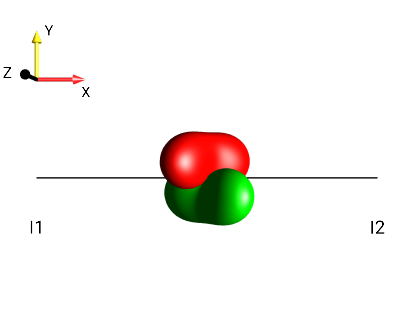

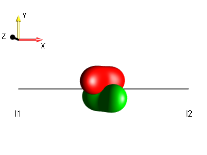

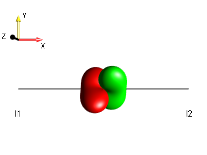

Head-tilt Rule¶

Based on the rules summarized on the previous page, a given droplet of an antiphase operator can be translated back into the form of a product operator (see challenges). As illustrated below, it is even simpler to recognize which of the involved two single spin operators is a \(z\) operator, i.e. to determine if the coherence is in antiphase with respect to the first or the second spin. Imagine the red and green lobes to be a pair of “kissing beans”. If the “heads” of the kissing beans are tilted to the left (relative to the z axis), the component of the first spin operator is \(z\) and the component of the second spin is in the transverse plane (i.e. the antiphase operator has the form \(±2I_{1z}I_{2a}\) with \(a \in \{x,y\}\) ). Conversely, if the “heads” are tilted to the right, the second single spin operator is a \(z\) operator and the Cartesian component of the first spin is in the transverse plane (\(±2I_{1z}I_{2a}\)). In the general case of operators involving spins \(I_m\) and \(I_n\) with \(m<n\), a tilt to the left indicates that the \(I_m\) operator is a \(z\) operator, and vice versa.

Left Tilt

Fig. 104 \(2I_{1z}I_{2x}\)¶ |

Right Tilt

Fig. 105 \(-2I_{1x}I_{2z}\)¶ |

Here, the “head-tilt rule” is shown for all antiphase operators involving spins I1 and I2.

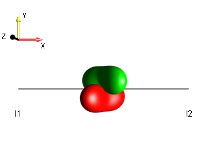

Left tilt: Antiphase coherence of spin I2 with respect to spin I1

Fig. 106 \(2I_{1z}I_{2x}\)¶ |

Fig. 107 \(2I_{1z}I_{2y}\)¶ |

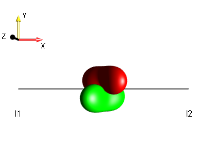

Fig. 108 \(-2I_{1z}I_{2x}\)¶ |

Fig. 109 \(-2I_{1z}I_{2y}\)¶ |

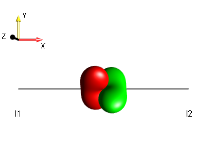

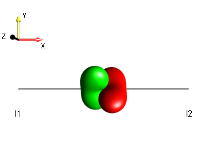

Right tilt: Antiphase coherence of spin I1 with respect to spin I2

Fig. 110 \(2I_{1x}I_{2z}\)¶ |

Fig. 111 \(2I_{1y}I_{2z}\)¶ |

Fig. 112 \(-2I_{1x}I_{2z}\)¶ |

Fig. 113 \(-2I_{1y}I_{2z}\)¶ |

Note

(By the way, an interesting study of human head-turning asymmetry appeared in Nature 421, 711, 2003, https://doi.org/10.1038/421711a)

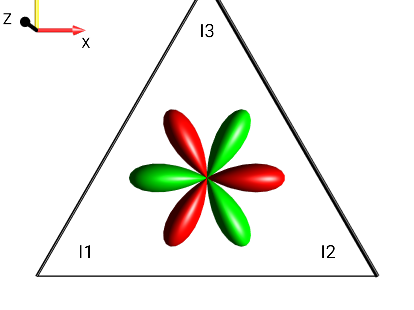

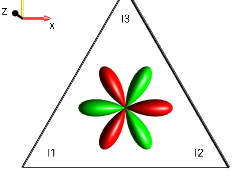

Droplets of Cartesian Product Operators Involving Three Spins¶

Tri-linear Cartesian product operators are represented by up to four droplets (\(τ_1\), \(τ_2\), \(τ_3\), \(τ_4\)) in the LISA Basis. Here, the DROPS Representation of characteristic Cartesian operators are displayed for the following cases: (a) three identical components, (b-d) two identical components and (e) all components different.

Fig. 114 \((a) \tau_1 \\ 4I_{1x}I_{2x}I_{3x}\)¶ |

Fig. 115 \((b) \tau_{1,2} \\ 4I_{1x}I_{2x}I_{3y}\)¶ |

Fig. 116 \((c) \tau_{1,2,3} \\ 4I_{1x}I_{2y}I_{3x}\)¶ |

Fig. 117 \((d) \tau_{1,2,3} \\ 4I_{1y}I_{2x}I_{3x}\)¶ |

Fig. 118 \((e) \tau_{1,2,3,4} \\ 4I_{1x}I_{2y}I_{3z}\)¶ |

Rotating Droplets Involving Three Spins¶

Based on the characteristic droplets for trilinear Cartesian Product operators shown on the previous page, the droplets of the remaining trilinear Cartesian product operator can be obtained by rotations around the x, y, or z axis (up to a possible change of sign, which simply corresponds to a change of colors).

For example, the operator \(4I_{1z}I_{2y}I_{3z}\) (where the first and last components are identical) can be obtained from the given operator (c) \(4I_{1x}I_{2y}I_{3x}\) by a non-selective 90° rotation around the y axis. Hence, the DROPS represen-tation of \(4I_{1z}I_{2y}I_{3z}\) can be found by rotating each of the droplets of \(4I_{1x}I_{2y}I_{3x}\) by 90° around the y axis.

Fig. 119 \(4I_{1x}I_{2y}I_{3x}\)¶ |

\(\Longrightarrow \\ \circlearrowright\) (90°y) |

Fig. 120 \(4I_{1z}I_{2y}I_{3z}\)¶ |

Droplet Symmetry and Coherence Order Rules¶

The droplet of an operator with well defined coherence order \(p\) can be easily recognized based on the following rules:

Rule 1 - Shape Invariance of Coherence Order¶

Disregarding the color, the shape of the droplet with a well-defined coherence order \(p\) is invariant under rotations around the z axis, i.e. the shape is not changed by a z rotation.

Rule 2 - Color Implies Coherence Order¶

The coherence order \(p\) of a droplet can be inferred from the color of a droplet, accoring to the following rules, 2.1 - 2.6.

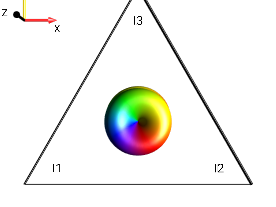

Rule 2.1 - \(p=0\) Droplets Are Invariant Around \(z\)¶

A droplet of coherence order \(p=0\) does not change its color if it is rotated by an arbitrary angle α around the z axis, as illustrated by the following examples in Table 14.

\(p\) |

Droplet |

z-Rot |

Droplet |

|---|---|---|---|

0 |

Fig. 121 \(I_{1x}I_{2x}+I_{1y}I_{2y}\)¶ |

\(\xrightarrow{\alpha_z}\) |

Fig. 122 \(I_{1x}I_{2x} + I_{1y}I_{2y}\)¶ |

0 |

Fig. 123 \(I_{1}^{+}I_{2}^{-}\)¶ |

\(\xrightarrow{\alpha_z}\) |

Fig. 124 \(I_{1}^{+}I_{2}^{-}\)¶ |

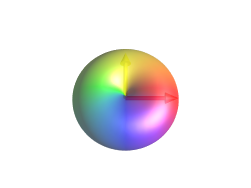

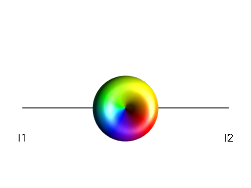

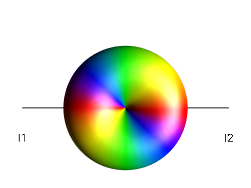

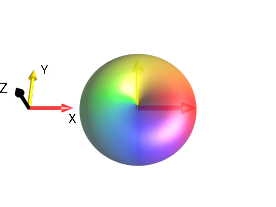

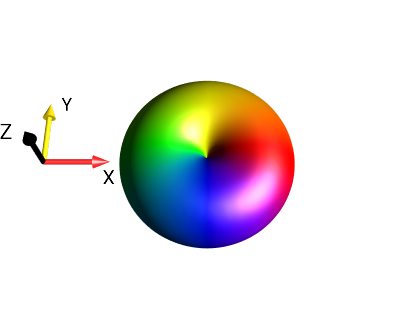

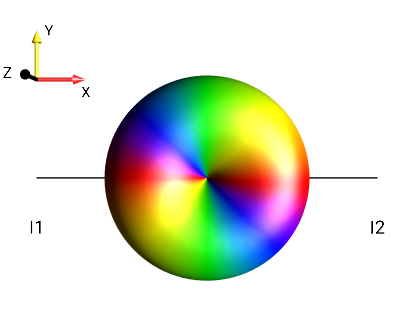

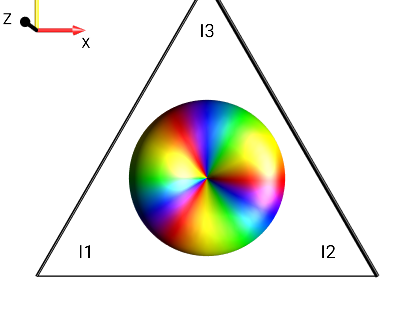

Rule 2.2 - Sign of Coherence Order¶

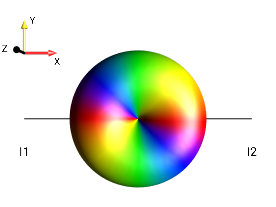

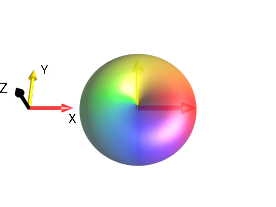

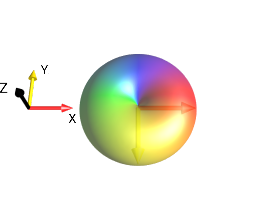

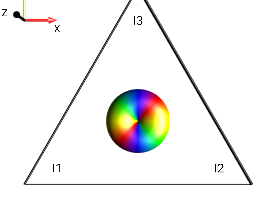

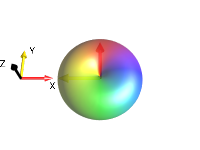

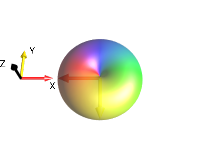

A droplet of defined coherence order \(p ≠ 0\) is rainbow-colored (where \(p\) is a non-zero integer with either positive or negative sign). For positive coherence order (\(p>0\)), the colors evolve from red to yellow to green to blue when moving counter-clockwise around the droplet. For negative coherence order, the colors progress in the opposite direction, as illustrated by the following examples.

Operator |

\(p\) |

Operator |

\(p\) |

Fig. 125 \(I_{1}^{+}\)¶ |

\(+1\) |

Fig. 126 \(I_{1}^{-}\)¶ |

\(-1\) |

Fig. 127 \(2I_{1}^{+}I_{2}^{+}\)¶ |

\(+2\) |

Fig. 128 \(2I_{1}^{-}I_{2}^{-}\)¶ |

\(-2\) |

Fig. 129 \(2I_{1}^{+}I_{2}^{+}I_{3}^{+}\)¶ |

\(+3\) |

Fig. 130 \(2I_{1}^{-}I_{2}^{-}I_{3}^{-}\)¶ |

\(-3\) |

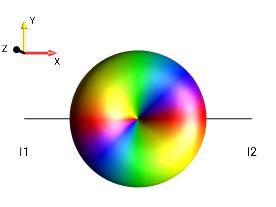

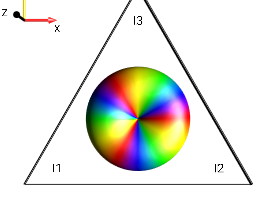

Rule 2.3 - Order of Coherence Order¶

For a non-zero, well-defined coherence order \(p\), the absolute value \(|p|\) of the coherence order of a droplet is simply given by the number of rainbows encountered when moving once around the z axis. Remember that according to (2.2), the sign of \(p\) is given by the direction that the rainbow progresses around the z axis, from red to yellow to green to blue.

Operator |

\(p\) |

Operator |

\(p\) |

Fig. 131 \(I_{1}^{+}\)¶ |

\(+1\) |

Fig. 132 \(I_{1}^{-}\)¶ |

\(-1\) |

Fig. 133 \(2I_{1}^{+}I_{2}^{+}I_{3}^{-}\)¶ |

\(+1\) |

Fig. 134 \(2I_{1}^{-}I_{2z}\)¶ |

\(-1\) |

Fig. 135 \(2I_{1}^{-}I_{2}^{-}I_{3z}\)¶ |

\(-2\) |

Fig. 136 \(2I_{1}^{-}I_{2}^{-}I_{3}^{-}\)¶ |

\(-3\) |

Rule 2.4 - Coherence Order Invariance under Z-Rotation¶

A droplet of coherence order \(p\) does not change its appearance if it is rotated by integer multiples of \(2\pi / p\) around the z axis. In the example shown below, \(p=+1\) and hence rotations by integer multiples of \(2π/(+1)= 2π =360°\) leave the droplet invariant.

Fig. 137 \(I_{1}^{+}\)¶ |

\(\{(π/2)\}_z = 90°z\) \(\Longrightarrow\) |

Fig. 138 \(exp(-i \cdot \pi /2) \cdot I_{1}^{+}\)¶ |

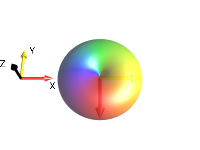

\(\{(π)\}_z = 180°z\) \(\Longrightarrow\) |

Fig. 139 \(exp(-i \cdot \pi ) \cdot I_{1}^{+}\)¶ |

|

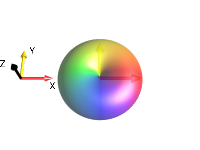

\(\{(3π/2)\}_z = 270°z\) \(\Longrightarrow\) |

Fig. 140 \(exp(-i \cdot 3 \cdot \pi /2) \cdot I_{1}^{+}\)¶ |

|

\(\{(2π)\}_z = 360°z\) \(\Longrightarrow\) |

Fig. 141 \(exp(-i \cdot 2 \cdot \pi ) \cdot I_{1}^{+}\)¶ |

Rule 2.4 pt. 2¶

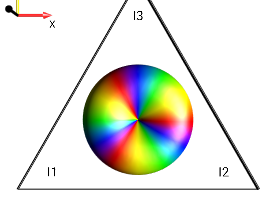

As stated in (2.4), a droplet of coherence order \(p≠0\) does not change its appearance if it is rotated by integer multiples of \(2π/p\) around the z axis. (Note that for \(p=0\), the droplet can be rotated by any angle around the z axis without changing its shape or color, as stated in properties (1) and (2.1).) This is illustrated by the examples shown below for well-defined coherence orders \(p\) of \(0, +1, +2,\) and \(+3\).

\(p=0\) |

Fig. 142 \(I_{1}^{+}I_{2}^{-}\)¶ |

Invariant under any rotation |

\(p=+1\) |

Fig. 143 \(I_{1}^{+}\)¶ |

Invariant under \(\pm 360°,\pm 720°,...\) |

\(p=+2\) |

Fig. 144 \(2I_{1}^{+}I_{2}^{+}\)¶ |

Invariant under \(\pm 180°,\pm 360°,...\) |

\(p=+3\) |

Fig. 145 \(2I_{1}^{+}I_{2}^{+}I_{3}^{+}\)¶ |

Invariant under \(\pm 120°\pm 240°,...\) |

Rule 2.5 - Hermetian Mixtures of Coherence Orders Under Z-Rotaion¶

Hermitian operators comprised of a mixture of coherence orders \(±p\) (such as \(±2\)) with \(|p|≠0\), do not change their appearance if they or their corresponding operators are rotated by integer multiples of \(2π/p = 360°/p\) around the z axis. This is illustrated by the examples shown below for coherence orders \(p\) of \(±1, ±2,\) and \(±3\).

\(p=\pm 1\) |

Fig. 146 \((I_{1}^{+}+I_{1}^{-})/2\)¶ |

Invariant under \(\pm 360°,\pm 720°,...\) |

\(p=\pm 2\) |

Fig. 147 \(I_{1}^{+}I_{2}^{+}+I_{1}^{-}I_{2}^{-}\)¶ |

Invariant under \(\pm 180°,\pm 360°,...\) |

\(p=\pm 3\) |

Fig. 148 \(I_{1}^{+}I_{2}^{+}I_{3}^{+}+I_{1}^{-}I_{2}^{-}I_{3}^{-}\)¶ |

Invariant under \(\pm 120°,\pm 240°,...\) |

Rule 2.6 - Sign Inversion of Hermetian Mixtures of Coherence Orders Under Z-Rotaion¶

Hermitian operators corresponding to a mixture of coherence orders \(±p\) (such as \(±2\)) with \(|p|≠0\), change sign if they are rotated by \(360°/(2p)\) around the z axis. Hence, after the rotation the shape of the droplet is unchanged but green lobes are now where corresponding red lobes were before the rotation. This is illustrated by the examples shown below for coherence orders \(p\) of \(±1, ±2,\) and \(±3\).

\(p=\pm 1\) |

Fig. 149 \((I_{1}^{+}+I_{1}^{-})/2\)¶ |

180° rotation

\(\rightarrow\)

|

Fig. 150 \(-(I_{1}^{+}+I_{1}^{-})/2\)¶ |

\(p=\pm 2\) |

Fig. 151 \(I_{1}^{+}I_{2}^{+}+I_{1}^{-}I_{2}^{-}\)¶ |

90° rotation

\(\rightarrow\)

|

Fig. 152 \(-(I_{1}^{+}I_{2}^{+}+I_{1}^{-}I_{2}^{-})\)¶ |

\(p=\pm 3\) |

Fig. 153 \(I_{1}^{+}I_{2}^{+}I_{3}^{+}+I_{1}^{-}I_{2}^{-}I_{3}^{-}\)¶ |

60° rotation

\(\rightarrow\)

|

Fig. 154 \(-(I_{1}^{+}I_{2}^{+}I_{3}^{+}+I_{1}^{-}I_{2}^{-}I_{3}^{-})\)¶ |